Not far from Minowa station on the Hibiya line is a nondescript temple called 浄閑寺—Jokanji. From the street, it looks like many other Tokyo temples, but behind the new main building is an old cemetery that has one particular point of interest, a crypt and monument to twenty-five thousand prostitutes interred there. Being so close to Halloween, I was looking for a spooky story when my friend Joe mentioned the place.

I didn’t find a ghost story.

I went looking for the quiet dignity of an old temple. What I unearthed instead was a ghost story written in blood, silk, and the hollowed out lives of the women who fueled Japan’s “Floating World.”

This is the story of Jokanji.

The Shadow of the Yoshiwara

To understand the story of Jokanji, you must first understand the gates of Yoshiwara.

This isn’t a history lesson, plenty of scholars have written about the Yoshiwara for years. This is about the cost. Behind those high walls, thousands of women and young girls were treated as a commodity for an insatiable lust of pleasure. They were the “flowers” of the district, but when the petals fell, when they were broken by disease, exhaustion, or despair, they ceased to be human in the eyes of the law.

The Temple of No Return

When a courtesan died without a family to claim her, there were no incense filled wakes or tearful processions. There was only the back gate. Her body, often wrapped in a simple straw mat, was literally tossed over the wall or delivered like refuse to Jokanji. This wasn’t a sanctuary for the living, it was a disposal site for the “used up.” It earned its grim moniker—Nage-komi-dera—because the dead were not buried so much as they were discarded.

A Witness in the Dark

My research into these grounds is a work in progress. It is a heavy, shameful ledger that I am still trying to balance. I’m currently tracing the footsteps of Nagai Kafu, a writer who refused to look away. His stories lived in the gutters and tea houses with these women, and his memorial stands nearby as a silent sentry to their memory. There is still so much to uncover. The names lost to time, the specific tragedies of the Meiji era, and the physical remnants of a history many would rather forget.

During the Tokugawa era, in present-day Taito-ku, Senzoku 4-chome, there was a licensed prostitution area called Yoshiwara. The area had been moved from near Nihonbashi in the late 1650’s after a devastating fire leveled much of the city and the new area was known for a time as Shin-Yoshiwara. (新吉原, New Yoshiwara, though eventually the “New” was dropped and people simply referred to the area as Yoshiwara.) For 300 years, the area was home to thousands of women and girls, many of whom were sold by their families as young girls.

Patrons approached via a long, curving street, a path designed to build anticipation, or perhaps to ensure no one could see the exit once they were inside. At the end stood the Great Gate, a massive structure not unlike the torii that guards a temple’s sacred ground. But there was nothing sacred about the commerce here.

Even the most fearsome Samurai were stripped of their dignity at the threshold. They were required to surrender their swords, before passing through. Inside, the only power that mattered was the weight of one’s purse, negotiated in the shadowy corners of nearby teahouses where lives were bought and sold over cups of steaming tea.

For the women, the walls were not a defense, they were a perimeter. Most had been sold into a debt so massive and so carefully calculated that it could never be repaid. They were prisoners of a ledger, bound by ink and blood to a life they never chose. Their world was reduced to a few square blocks of lantern-lit streets. Their freedom was measured in moments, not miles. They were permitted to leave only upon the death of a parent. Once a year, they were escorted to Ueno to view the cherry blossoms—a cruel reminder of a beauty that blooms and dies in a single season.

For the thousands of common prostitutes who worked in this pleasure quarter, there was no retirement. There was no “buying back” their lives. The walls of Yoshiwara were absolute.

For them, the only real way out wasn’t through the Great Gate or the cherry orchards of Ueno. The only true exit was the one that led to the Throw-Away Temple. Their only escape was through the silence of their own death.

On on November 11, 1855 the Ansei Edo Earthquake (安政江戸地震, Ansei Edo Jishin) a 6.9 magnitude earthquake struck Edo (The old name for Tokyo) with intermittent aftershocks over the next two weeks. The last major quake to hit Edo had been in 1703, so few if any of the residents of the area had ever experienced a major quake and hadn’t given any thought to earthquake safety.

Buildings collapsed and fires spread rapidly through the city. Unfortunately for the women enslaved in Yoshiwara as common prostitutes, if they had survived the building collapses, they were far more likely to die in the resultant fires. Yoshiwara, after all, was a walled village with only two exits, both narrow, to control the passage of people in and out. Fear of looting slowed the evacuation as well.

Woodcuts I examined at the Taito-ku Library in Kappabashi showed the fates of some of the different classes of people in Yoshiwara—one showed an elegantly-dressed Oiran or high-level courtesan being rushed from the area by two samurai. One samurai was on horseback and both had their swords, indicating that they had been dispatched to rescue this woman, as swords were not allowed in the quarter, even for samurai who were habitués of the brothels. Another print showed lower-class prostitutes clad in the common plain blue kimono that was mandated for working girls. (This rule was ignored by those whose status was higher.) The prints showed the lower classes, both men and women, panicking in the streets, crushed by heavy roof tiles and buildings, crawling through the streets in despair. One showed the interior of a brothel as it collapsed, women and customers tossed about mid-coitus, while a prominent sign on the wall says “火の用心” or “Be careful of fire.” Another showed looters, some themselves trapped under rubble, greedily swallowing gold and silver coins and later “recovering” them as they passed through their systems.

At the time it was a commonly held belief that earthquakes were caused by an imbalance of the good and evil forces of Yin and Yang, so a major quake, to some, was a sign that social change was needed. (Often referred to as “correlative cosmology”.) The quake was centered northeast of the city and Yoshiwara, too, was northeast of the palace. In Buddhist tradition, the Northeast is known as “Kimon” or the direction that bad luck follows. In 1855, the Northeast of the city was the hardest hit by fires, with the West of the city largely untouched. Yoshiwara in particular was among the worst hit.

Yoshiwara went into a decline and the brothel owners’ profits fell. To counter this decline, the owners brought in more women and lowered prices. Conditions worsened and disease became the norm. The numbers tell a story that the woodblock prints try to hide. In 1700, the Yoshiwara held fifteen hundred souls within its walls. By the dawn of the 20th century, that number had exploded to nine thousand women, all crushed into the same suffocating quarter.

As the population swelled, the air inside the district grew thick, not with perfume, but with the scent of decay. In the cramped, damp corridors of the lower tier brothels, disease was the only constant companion.

- The White Plague: Tuberculosis hollowed out their chests, leaving them coughing blood into silk handkerchiefs.

- The Great Pox: Syphilis rotted them from the inside out, a slow, agonizing payment for debts they never truly owed.

- The Fever: When Typhoid swept through the quarter, it moved like a scythe through dry grass.

For the common prostitute, there was no such thing as “growing old.” To reach one’s thirtieth birthday was a feat of survival that few ever achieved. They were the fuel for a machine that ran on youth and discarded the ashes. While historians and artists might drape this era in gold leaf and romanticize the “glamour” of the Meiji-era courtesan, the reality was a brutal, high-speed meat grinder. The industry spoke of “turnover,” a sterile word for a horrific reality. As quickly as a girl was broken by sickness or despair, another was brought in to take her place. They were treated as interchangeable parts in a grand, neon-lit engine of misery. The “glamour” was a mask, a thin layer of white powder painted over a face wasted by fever, hiding a life that would likely end in a straw mat at the back gate of Jokanji long before the first grey hair appeared.

At the time of the Ansei quake in 1855, there was a severe shortage of coffins, so much so that people resorted to using sugar casks and barrels as makeshift caskets for even the more wealthy of the dead, so for someone of such low social status as a common prostitute, there would be no such ceremony. Bodies were simply piled until they could be disposed of.

This certainly must have set a precedent for later. When a woman of Yoshiwara died, she died with little pity or notice. Brothel workers would take her body, wrap it in a cheap rush mat, carry her out and dump her at the gates of the nearby Jokanji temple. In all, an estimated 25,000 women were thusly interred. The practice became so common that the temple became known as “Nage Komi Dera,” (投込寺,) the “Throw-in Temple” with all of the connotations of being a dumping ground for unwanted, forgotten women.

Why Jokanji was chosen isn’t clear. It’s not the nearest temple and getting there while carrying a body would have required a fairly roundabout route, at least using the paths shown on maps of the times. Yoshiwara itself was surrounded by rice fields, fairly impassible most of the year. In November, the rice would have been cut to stalks and the ground itself a thick, sticky muck.

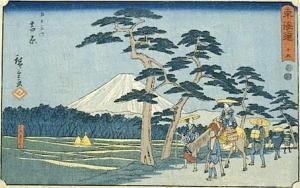

The most direct route would have required the use of the front gate, which I find hard to imagine, as it would have been quite bad business to carry dead prostitutes past incoming customers. More likely, the back entrance was used. A woodcut from the time by Hiroshige shows the area, with its narrow roads between the rice paddies.

View of Mt. Fuji from Yoshiwara, from Hiroshige’s 53 Stations of the Tokaido. This is be a Southwest-facing view, therefore from the rear exit of Yoshiwara. The visible road leads away from Jokanji, which is to the North. Most likely, they used unmarked service paths between the rice fields which would have offered a direct and discreet route straight to the temple, avoiding the streets.

Another view of Mt. Fuji from Yoshiwara, from Hiroshige’s 53 Stations of the Tokaido. In this view, walkable paths in the fields are visible. These paths do not appear on period maps, but may have afforded a passible, discrete route from Yoshiwara to Jokanji.

(Note: a reader has noticed a discrepancy with the accuracy of the old prints. We are looking into it now, cheers)

Around the turn of the century, as Japan opened up after the Meiji Restoration, international pressure started to force some changes to the area. By Meiji 38, (1905,) the practice of dumping bodies there was largely stopped and a monument to the women was erected at Jokanji, but it’s reputation as a dumping ground and the nickname “Throw-in Temple” (nege-komi-dera) stuck.

When I first went looking for the place, I wandered a bit before asking a pair of shopkeepers for directions. “I’m looking for Jokanji. A temple in this area…”

“Jokanji? I don’t know it…” the more senior of the two said.

“It’s the throw-in temple,” the assistant offered. “not far from here.”

“Ah, yes—of course!”

He pointed me toward a quiet corner of the neighborhood, and I hopped on my bicycle and cycled a few blocks over. When I finally pulled up to the entrance of Jokanji, I felt a little skepticism. The building was sleek, modern, and polished, not at all the crumbling, atmospheric ruin I had prepared myself for. I locked my bike, wondering if I had chased a ghost into a dead end.

I stepped through the gates, and to my left, a long wall guarded the cemetery. I walked into the maze, expecting to see a landscape of tragedy, but instead, I found the quiet, cramped geometry of an ordinary Japanese graveyard.

Row after row of family monuments stood in narrow, well tended lanes. It was a mundane sight that forced a realization. Jokanji wasn’t a temple built for the Yoshiwara, it was an ancient anchor that the Yoshiwara had simply drifted past. Most of the families resting here likely had nothing to do with the mizu shobai, the “water trade” of the sex industry. It was just a neighborhood cemetery doing its somber, eternal job.

I must have looked lost, or perhaps I just had the specific, haunted look of someone searching for a tragedy in a place of peace.

A temple worker, busy with his rounds, caught my eye. He didn’t wait for me to find the words. He simply waved a hand toward the far back of the grounds. “It’s over there,” he said, his voice flat with the casualness of someone who directs seekers to a mass grave every day of the week.

I followed his gesture and turned the corner. The shift was immediate.

The monument loomed out of the shadows, massive and heavy, dwarfing the family stones nearby. It was an unmistakable weight of history. But the worker wasn’t done. He walked me further down the lane toward a large, sprawling tree.

“The old entrance to the graveyard was just beyond that tree,” he explained, his tone dropping into something more solemn. “That’s where they did it. That’s where the bodies were typically dumped.”

I looked at the ground beneath the branches through the sunlight. But in my mind’s eye, I could only see the straw mats being slid off carts in the dead of night, discarded in the dirt like yesterday’s news.

It’s a grim place on a late October day, so close to Halloween, though there are fresh flowers every few days and ritual incense is burned each day. On the left are sotoba, the wooden sticks that typically bear the deceased’s Kamiyo, the name the person is given after death in the Buddhist tradition. (As most of the souls inside were anonymous, I don’t know whose names are upon these sticks.)

Each day I went there to photograph the place, I’d see a couple of Japanese sight-seers come by with digital cameras to take a few snapshots.

Atop the monument is a seated Buddha holding a staff with six rings affixed to the top. The pillar behind is deeply inscribed “Shin-Yoshiwara-Soureitou,” (新吉原總霊塔) roughly meaning simply “Shin Yoshiwara Memorial.” An older photo of the memorial shows the pillar alone, sitting atop its stone lotus base, indicating that the Buddha figure was added later.

A small shrine sits at the base in the front, with an offering plate (¥7 was in it when I visited) and a place to burn incense, cups of sake and flowers.

Above the standing figure is a red lacquer ‘Hira-Kanzashi’ hair ornament of the type a girl in Yoshiwara might possess, affixed to the wall.

Hira-Kanzashi’ hair ornament

Along one side there are a couple of small, barred windows, through which you can see earthenware pots containing the ashes of some of the people interred there. Along the other side is a locked iron door, leading to the interior of the crypt. Through the bars, if you let your eyes adjust for a few minutes, you can see that it’s quite large inside. Just inside the door is an iron ladder leading down about three meters to the floor. The walls are lined with shelves on which the pots were stored, but for the most part, empty, as the jars most likely fell and broke in later earthquakes.

Crouching near the window of the door, trying to get a photo, I could smell the interior of the crypt, a cool, earthy smell. It’s much like the smell of an earthen basement, but not quite. It was a familiar smell though, one I’d smelled before, but couldn’t place. I realized after a bit where I’d smelled it before – it was the scent of the bones I’d smelled in the catacombs below Paris. Matt Treyvaud, of No-Sword was kind enough to provide a translation of part of the inscription on the Nagai Kafu memorial I mentioned. I don’t know a lot about Nagai, so I felt remiss in neglecting him; I’m happy to have this, as he’s obviously an important chronicler of the place and time.

Young people of this world

Do not ask me about this world’s

Art or arts of any times to come.

Am I not a child of Meiji?

When those ways became history, were buried,

The dreams of my youth vanished too

The last of Edo’s ways are become smoke.

Meiji culture, too, is become ash.

Young people of this world

Do not speak to me of this world’s

Art or arts of any times that may come.

I could clean my clouded glasses

But what could I then see?

Am I not a child of Meiji?

Am I not a child of long-ago and long-gone Meiji?

I had hoped to dig into that a bit more, but haven’t yet had a chance, so I appreciate his help in this.

On another note, as we walked through Minowa, Jokanji and Yoshiwara today and at the end of the day we exited Yoshiwara through what was once it’s back gate and found ourselves at the spot from which Hiroshige had drawn the first image in this post:

I have no doubt that it’s the same spot as in 1830, there was no other road leading from that side of Yoshiwara. Luckily I have an image on my ipod for reference and it was a remarkable moment.

Thankyou to Jim for writing about this topic, as sad as it is.

Edited for Rekishinihon by Stuart.

Reblogged this on 夢日記 and commented:

This is a really fascinating article on an area of Japanese history I must admit to not being particularly aware of.

LikeLike

Thankyou for reading.

LikeLike

No problem! You’ve given me another place to visit while I’m in Tokyo.

LikeLike

Hi, I found your site through one of Facebook pages and I am really curious about the old Japan, so this has been a very interesting article. 25.000 women…It’s extremely tragic…I would like to read the novels by the author mentioned above on these Yoshiwara people.

LikeLike

I have noticed you don’t monetize your blog, don’t waste your traffic, you can earn additional bucks every month.

You can use the best adsense alternative for any type of website (they approve all websites),

for more info simply search in gooogle: boorfe’s tips monetize your website

LikeLike

Moncler | Men’s Women’s Coats & Jackets for Sale Luxury Fashion �C lassic moncler jacket outlet Online Sale. A collection of 100 items moncler jacket outlet Free Worldwide Shipping!

[url=http://www.canadagooseonlinesale.com/]Canada Goose Jackets Sale USA[/url]

Canada Goose Jackets Sale USA

LikeLike

Thank you for writing this. It’s so very sad. I hope to visit someday myself.

LikeLike

Yes, it is a sad part of Edo life and the Yoshiwara district. Thankyou for reading.

LikeLike