Ancient Northern Mariners, Traders and Raiders in the Sea of Okhotsk.

For centuries, the Sea of Okhotsk was a realm of ghosts and grey mists. It was a frozen frontier that the Shogunate had not yet conquered, but as the 1700s waned, the unknown northern wilderness began to open up and offer an abundance of new opportunities to those who were adventurous enough to brave the harsh conditions.

From the jagged spine of the Kuril Islands, bearded men in heavy furs, Russians began their steady creep southward. On the rocky shores of Hokkaido, early Japanese settlers stood their ground, ready to drive the northern invaders back into the ocean.

Yet, as the 18th-century quickly arrived and the odd skirmish with old foes cleared, a deeper truth emerged from whispers of neighbouring empires. Long before the Shogun or the Tsar turned their eyes to these icy waters, a different breed of explorer ruled the waves.

As early as the 6th to 7th century, the Ainu of Hokkaido were the true masters of the north. In stout, hand-hewn vessels, they defied the freezing ice and howling gales, sailing the treacherous currents to carve out a maritime empire. They weren’t just survivors, they were conquerors of the horizon, penetrating deep into the wilds of Sakhalin, leaping across the Kuril island chain, and taming the volcanic reaches of the Kamchatka Peninsula centuries before the modern world even knew they were there.

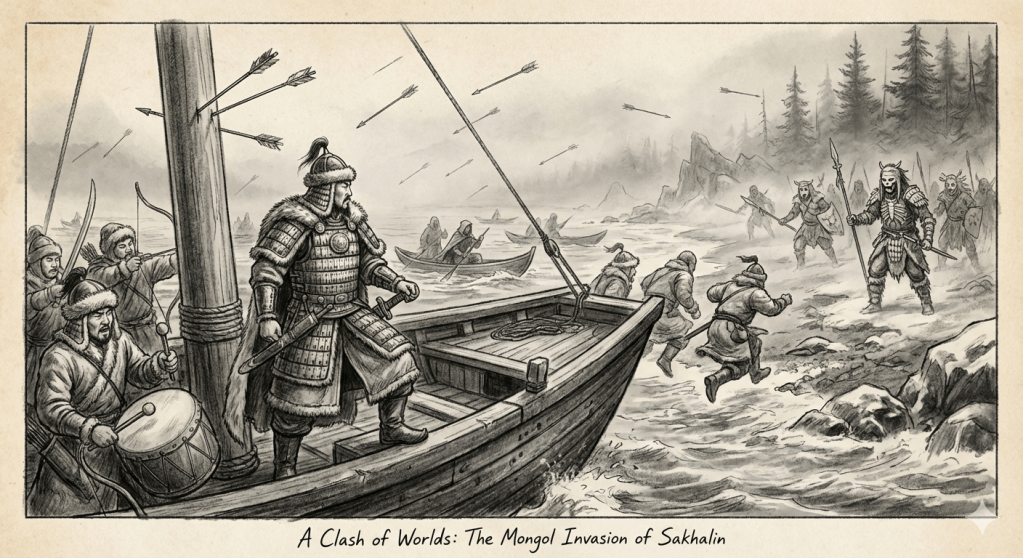

The year was 1263, and the shadow of the Golden Horde had finally reached the edge of the world.

Kublai Khan, fifth ruler of the Mongol Empire and master of the Steppe, turned his insatiable gaze toward the freezing lower reaches of the Amur River. Like a slow moving glacier of iron, his forces swept through the north, crushing the Jurchen and Nanai tribes beneath the weight of the Yuan Dynasty. Even the Nivkh, the hardy souls dwelling at the river’s mouth and across the treacherous straits of Sakhalin, were forced to bow before the Great Khan’s banner.

But the frontier remained restless.

According to the History of the Yuan Dynasty, a desperate plea reached the Khan’s commanders in 1264. The Gilimi people, now subjects of the Empire, came with a blood soaked grievance, the Kugi warriors of Sakhalin had crossed the water, invading pillaging their lands, defying a restless Mongol peace.

The response was swift and brutal.

One year after the Amur fell, the Mongol war machine took to the sea. They launched a punishing invasion of Sakhalin, hunting the Kugi into the frozen heart of their island. It was more than a border skirmish, it was a clash of worlds, where the unstoppable force of the Mongol cavalry met the fierce, maritime and ghost like resistance of the north.

The mist over the Tatar Strait was thick as wool, hiding the jagged coastline of Sakhalin. On the deck of a heavy, flat-bottomed Yuan transport ship, Commander Toghon gripped the hilt of his sword. Around him, the Mongol cavalrymen who had conquered the sun-scorched Gobi shivered in the biting salt spray of the north sea.

They were far from their horses’ grazing lands, following the desperate plea of the Gilimi tribes.

They think the sea is their fortress, but they forget the Khan owns the horizon! Icy water groaned against wooden hulls. Through the fog, the first signs of the enemy appeared, not a wall of stone, but a fleet of swift, narrow Kugi canoes. These were the warriors the Gilimi feared the “Kugi,” known to history as the fierce Ainu ancestors of the north.

Ready the archers! Toghon, the Mongol commander yelled, breaking through the icy wind.

A whistle pierced the air. A flight of Kugi arrows, tipped with poison and obsidian, rained down through the mist. One struck the mast with a dull thud.

“Sound the drums!” Toghon roared.

The heavy Mongol drums began a rhythmic thunder that echoed off the cliffs of Sakhalin. The Yuan soldiers didn’t wait for the ships to beach, as the bow ground into the freezing sand, they leapt into the surf.

From the tree line, the Kugi emerged like ghosts. They wore armour of toughened hide and bone, their faces painted for a war of survival. They didn’t fight like the armies of the plains, they moved like the tide, striking hard and vanishing back into the dark pines.

The sand turned dark, not from the tide, but from the first blood spilled of an imperial war. The shoreline was icy but manageable, however, just a few feet from the beach snow piled knee deep. The Great Khan had demanded an island, but as Toghon watched his men struggle through the deep northern snow, he realized the Kugi would make them pay for every inch of it in blood.

In this era, the Mongol Empire used a mix of Chinese-style naval technology and northern conscripts to bridge the gap between the mainland and the islands. The Kugi were formidable opponents because their guerrilla tactics in the dense forests negated the traditional Mongol advantage of open-field cavalry charges.

Who were these ancient warriors so adapted to the harsh environment?

The term Gilimi (吉里迷) is the pronunciation of Gillemi, the name used by the Nanai people of the lower Amur River to refer to the Nivkh. When Russian explorers arrived in the region during the seventeenth century, they referred to this same group as the Gilyak. Today, the Nivkh population remains at approximately 4,500, centered around the mouth of the Amur and northern Sakhalin.

Similarly, Kugi (骨嵬) is the pronunciation of Kughi, which is the Nivkh name for the Ainu. Among the Tungus peoples of the lower Amur, the name was pronounced Kuyi. This variation was eventually adopted into Chinese and recorded as Kui (苦夷) during the Ming Dynasty (1368–1644).

Not only did the freezing cold environment affect population changes, so did war. During the Edo Period (1603–1868) approximately 2,500 Ainu inhabited southern Sakhalin. Fast forward a hundred years, during Japanese Rule (1905–1945) and following the Russo-Japanese War, the Ainu population in southern Sakhalin was recorded at roughly 1,500.

The long-held myth that the Ainu had always dwelled in the frozen silence of Sakhalin has finally been unearthed. Modern archaeological excavations biting deep into the permafrost, have found a different truth, in the thirteenth century, these northern shores belonged entirely to the Nivkh.

The Ainu were not mere inhabitants, they were a rising tide. From their ancestral strongholds in Hokkaido, Ainu war parties began a fierce expansion northward, carving a path into Sakhalin and driving the Nivkh back toward the mouth of the Amur.

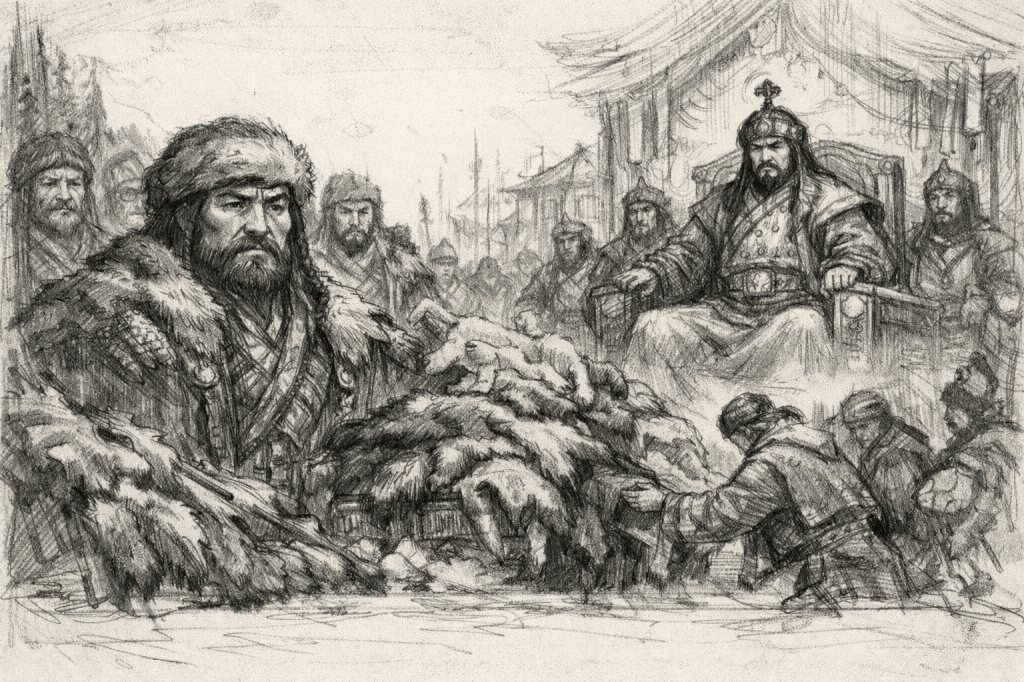

By 1265, the frontier reached a breaking point. The Yuan Shi, the chronicles of the Great Khan, records a brutal skirmish where the Kugi fell upon a band of Gilimi (Nivkh) warriors, leaving only corpses in the snow. The news reached the Mongol courts, but the response was not the iron fist the world expected.

Instead of unleashing the Horde’s fury, the Mongols played a deeper, more dangerous game. They saw in the Ainu a ferocity they respected and perhaps a maritime shield they desperately needed. To the shock of their allies, the Mongols met the defiant Ainu not with fire, but with open palms. They offered mountain high piles of grain, finely honed steel blades, and suits of lacquered armour.

It was a gamble of empires, the Great Khan was attempting to bribe the very wolves who had bitten his subjects, hoping to turn the Ainu’s unstoppable expansion into a weapon for the Mongol throne.

Yet, the Great Khan’s diplomacy failed, the time for giving was over, and the time for war had begun.

In 1271, having ascended the throne as the emperor of the newly forged Yuan Dynasty, Kubilai Khan looked toward the grey mists of the Tatar Strait. He demanded the total submission of the Kugi. In 1272 and again in 1273, he unleashed great expeditions, fleets of heavy ships carrying the finest warriors of the steppe. But the sea itself seemed to fight for the Ainu. The treacherous currents and howling northern gales held the Mongols at bay, forcing the Great Khan’s armadas to retreat before they could even set foot on Sakhalin’s shores.

The Khan, however, was a man of infinite patience and mountain shaking resolve. A decade later, he struck again with the full weight of the empire. Through the winters of 1284, 1285, and 1286, three massive invasions hammered against the island’s defences. Finally, the Kugi’s lines buckled. Under the shadow of Mongol banners, the island was declared won.

But the Kugi were cunning, they might be pushed back, but they would always return.

Defeat only fanned the flames of Kugi defiance. In a daring reversal that stunned the Yuan commanders, the Kugi warriors launched their own counter-invasions. In 1296, 1297, and 1305, they took to their swift shallow hulled vessels, crossed the deadly strait, and carried the fire of war back to the Eurasian continent itself. They struck at the heart of the Mongol frontier, ghosts of the mist raiding the outposts of the world’s greatest empire.

The Yuan imperial record of the Mongol dynasty betrays the frustration and begrudging respect of the conquerors. To finally crush the spirit of the island warriors in 1286, the Khan was forced to summon a leviathan of war.

The annals claim an armada of one thousand ships was launched, carrying a staggering force of ten thousand seasoned soldiers. They were sent to put an end to a resistance that refused to die. While court historians may have inflated these numbers to mask the embarrassment of such a long struggle, the legend remains. It took the might of an empire to silence the Ainu’s war cries. Even as the massive fleet choked the horizon, it served as a permanent monument to the tenacity of a people who fought the world’s greatest army to a standstill for nearly half a century.

It took nearly forty years of blood to reach the end. In 1308, the long war finally cooled into a hard won peace. The Kugi at last submitted to the Yuan, but they did so as a people who had looked the Great Khan in the eye and refused to blink. From that year on, a tribute was paid. A king’s ransom in luxurious furs and pelts, flowing from the wild forests of Sakhalin to the golden halls of the Khan.

For forty years, the Ainu of Sakhalin did the unthinkable, they defied the unstoppable momentum of the Mongol Empire. While the Khan’s horsemen had trampled the great cities of the Silk Road and brought the kings of Europe to their knees, they found themselves locked in a gruelling, four-decade stalemate against masters of the northern frozen lands.

A new threat for the Ainu

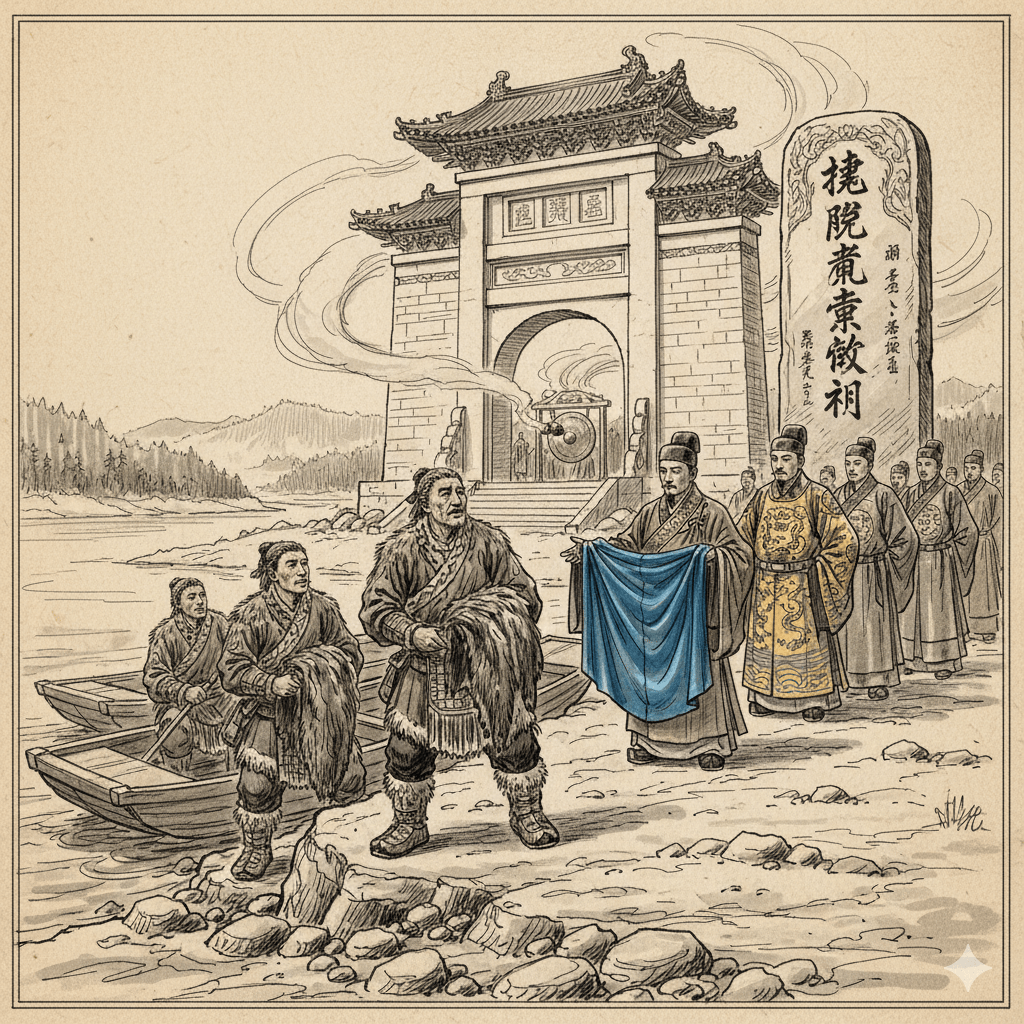

The winds of the north shifted once more in 1368. The Mongol giants, who had ruled the world for a century, were finally driven from China, leaving a power vacuum that the rising Ming Dynasty was eager to fill. By 1387, the Ming banners had reached the frozen banks of the lower Amur, claiming the wild frontier for a new Emperor.

But the true test of Ming ambition came in 1411. The legendary Yongle Emperor, a man of relentless grand visions, dispatched a massive expedition to the mouth of the Amur. Their mission was to plant a flag at the edge of the world. In the remote outpost of Nurgan, they established a seat of imperial power, and in 1413, they built the Yongning Temple Stele, a towering Buddhist temple at Tyr, 153 kilometres from the sea.

The local tribes, however, did not bow easily. The Nivkh and their allies, seeing this temple as a foreign splinter in their land, rose up and burned Yongning to the ground. Yet, the Ming were relentless. By 1433, the temple rose again from the ashes, a monument to imperial persistence. In the heart of Nurgan, the Chinese erected a massive stone stele, a silent sentinel etched with the history of their rule. The stone told of a strange and historic gathering, emissaries from the valley and the fierce Kui, the Ainu of Sakhalin, had crossed the treacherous Tatar Strait to meet the newcomers.

There, amidst the swirling snow and the smell of incense, the Ainu received the emperor’s bounty, fine silk clothing, iron tools, and stockpiles of food. It was a diplomatic masterstroke. To the Ming, these were not merely gifts, they were the “golden handcuffs” of empire. By accepting the emperor’s hand, the Ainu had entered a pact, agreeing to return through the mists with a tribute of furs and riches, acknowledging that a new sun had risen over the Northern seas.

The mist clung to the Amur River like a shroud, but as the Ainu longboats rounded the bend at Tyr, the fog suddenly parted.

High atop the escarpment, the Yongning Temple loomed over the water, a startling burst of crimson wood and gold leaf against the jagged grey cliffs. It was a structure of impossible geometry, its tiered roofs sweeping upward like the wings of a mountain hawk.

Shiramba, a seasoned Ainu elder whose face bore the scars of a dozen Sakhalin winters, signalled his rowers to slow. Beside him stood a young warrior, clutching a bundle of sea-otter pelts. Both men stared in silence.

The young warrior whispered to Shiramba, ‘the Nivkh said they burned this place to the dirt. They said the spirits of the river had swallowed the foreigners’ stone.’

Shiramba replied, ‘They did. But these southern men… they do not accept the river’s answer. They build on the bones of their own failures.’

As their vessels touched the rocky riverbank, the air was filled with a sound the Ainu had never heard. It was the deep, resonant drone of a Buddhist gong. It vibrated through the hull of their boats and into their very spirit. Standing before the temple gates was a line of Ming officials in heavy, embroidered robes that shimmered with threads of real gold. Behind them stood the “Silent Sentinel”, the great stone stele, its surface fresh with sharp, black ink.

The Ainu traders stepped onto the shore, their bear-hide boots crunching on the frost. A Ming emissary stepped forward, holding out a robe of sapphire silk so fine it looked like captured water.

Shiramba whispered to himself, ‘The silk is soft, but the iron behind it is cold, no doubt.’

He looked up at the temple one last time. It was a beautiful, but he knew that by stepping through those gates and accepting the emperor’s silk, the world of the North was changing forever. The mists would no longer belong only to the spirits, they now belonged to the mapmakers of the Ming.

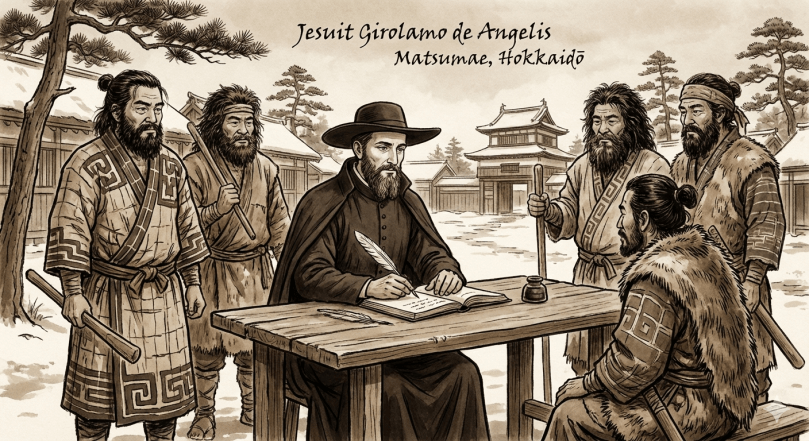

By the dawn of the seventeenth century, the “Land of Yezo” remained a jagged mystery to the Western world, a realm of ice and spirits at the edge of the map. But where soldiers and merchants feared to tread, the black-robed shadows of the Jesuit Order moved with quiet, relentless purpose.

The first to brave the northern frontier was the Italian Girolamo de Angelis. Arriving in Japan in 1602, he spent years navigating the high stakes politics of Kyoto and Sunpu before the call of the wild north became undeniable. In 1615, he pushed into the Tohoku wilderness, moving through Sendai like a ghost among the pines.

By 1618, de Angelis did the unthinkable, he crossed the hazardous straits into Hokkaido. Amidst the smoke of Ainu hearths and the scent of cedar, he became a silent observer of a world unknown to Europe. Twice he ventured into these forbidden lands, his ink-stained fingers recording every detail of the Ainu people and their rugged terrain in secret, detailed reports dispatched to his superiors.

He was soon joined by a brother-in-arms, the Portuguese firebrand Diogo de Carvalho. Having cut his teeth in the southern heat and humidity of Kyushu, Carvalho trekked north in 1617 to meet de Angelis in Sendai. The two missionaries became the eyes of the West in the frozen north. Carvalho followed the trail into Hokkaido in 1620 and 1622, his own letters home painting a vivid, haunting picture of the “Land of Yezo.”

These were more than just religious reports, they were the first true intelligence briefings on a frontier that was about to become the centre of a geopolitical storm. Through the quill strokes of these two men, the mystery of the Ainu began to bleed into the consciousness of the world.

The wind howled through the slats of a weathered mountain hut on the outskirts of Sendai. Inside, the air was thick with the scent of pine smoke and damp wool. On a low table sat a single, guttering candle, its flame dancing between two men who looked more like rugged explorers than men of the cloth.

Girolamo de Angelis unrolled a sheet of thick washi paper. His hands, calloused from the freezing Hokkaido winds, smoothed the edges. Beside him, Diogo de Carvalho leaned in, his face etched with the exhaustion of the long trek from the southern coast.

Carvalho, tracing a line with his finger, explains to Girolamo, ‘the currents here, Girolamo… they are not like the waters of Kyushu. They are freezing cold and currents pull toward the northern void. Did you find the crossing as treacherous?’

‘The strait is a beast that never sleeps, Diogo. But look here, beyond the peaks of Yezo. The Ainu speak of lands further still. Islands like stepping stones leading into the fog.’ He replied.

De Angelis dipped a quill into a small vial of ink. With a steady hand, he sketched a jagged coastline that no European map had ever dared to name.

De Angelis continued, ‘they call it the land of the mists. I have seen their hunters return with furs that shine like silver. They are not merely tribesmen, they are a bridge to a world we haven’t even dreamt of.’

‘And the Shogun? Does he know his northern gate is so wide open?’ Carvalho asked.

‘The Matsumae lords watch the coast, but the heart of the land remains wild. We are the first to put ink to this silence, my friend. If these letters reach Rome, the map of the world changes tonight’ replied De Angelis.

Carvalho pulled his cloak tighter as a fresh gust of snow rattled the door. He looked at the ink drying on the page, a spiderweb of lines representing a frontier that was no longer a myth, but a reality they were now bound to.

My Travels in the Land of Yezo: A Report by Jesuit Girolamo de Angelis

‘I have taken up residence in Matsumae, a Japanese castle town situated at the southernmost tip of Hokkaido. It is here that I first encountered the Ainu or Yezojin, as the Japanese call them. By observing their customs and gathering their testimonies, I have begun to piece together the nature of this mysterious Land of Yezo.’

Observations on Trade and the Menasi

‘Each year, a fleet of one hundred ships arrives here from Menasi in the east. They come heavily laden with salmon and herring, but their most curious cargo is the pelt of an animal called the rakko (sea otter). While similar to the sable, these creatures are not native to Yezo; rather, they are found around the distant Rakkojima, or as we call it, Otter Island.’

‘The Yezojin of Menasi must travel a great distance to Rakkojima to purchase these pelts. They tell me of many other islands in that vicinity, though the inhabitants there differ from the Yezojin, they possess skin that is not as white, nor is their hair remarkably bushy. The Yezojin themselves are a hairy people, wearing their hair in long tresses that hang well below their shoulders. Just last year, two individuals from those distant islands arrived in Matsumae, yet they remained a mystery to us, as no one could decipher a single word of their tongue.’

Northern Trade and the Mystery of Silk

‘From the northern reaches of Teshio, other Yezojin arrive in their boats. They bring a variety of goods, most notably a large quantity of ornate, finely woven silk. These textiles bear a striking resemblance to the craftsmanship of China.

In my second report, I have included a map depicting Yezo as an enormous island lying just north of Honshu. Based on my observations, the western tip, near the Teshio region lies just across a narrow strait from the Asian continent, likely near Korea or northeastern China.

In conclusion, seeing the proximity of the coast and the quality of the garments, I initially assumed these silks reached Yezo directly from China. However, I must consider the role of the Kugi (the Sakhalin Ainu). It appears more probable that these textiles are the same silk robes given to them in exchange for tribute at the Ming outpost in Nurgan, eventually filtering down to us through Sakhalin.’

My Observations in Matsumae: The Account of Diogo Carvalho

‘Like my companion de Angelis, I have spent significant time here in the castle town of Matsumae. By staying at this southern gateway, I have been able to observe the various peoples of Yezo and record the particulars of their commerce and way of life.

I have seen the Yezojin arrive from the far northeast, their boats finally pulling into harbour after, what I suspect to be a gruelling journey of more than sixty days. They carry with them, the highly prized rakko furs, extraordinarily soft pelts sourced from the distant Otter Islands.

Beyond these furs, they provide the Japanese with the tools of war and prestige. I watched them unload live hawks and vast quantities of eagle feathers, which the Japanese craftsmen prize above all else for fletching and decorating their arrows.

The reach of Matsumae’s trade extends even further than I first imagined. I have met travellers from the extreme north who endure an even more arduous passage, journeying by sea for more than seventy days to reach this port.

What struck me most was the cargo they brought from such a rugged, distant land, silks of a very fine quality. These are not the rough garments one might expect from the northern wilds, but delicate, expertly woven textiles that suggest a connection to great empires further beyond our current maps.’

Ultimately, the testimonies of Girolamo de Angelis and Diogo Carvalho reveal a truth that defies the isolation of the snowy north. We find ourselves not at the end of the world, but at the centre of a thriving, frozen crossroads.

Observations from the Jesuits establish a picture of lively trade of goods flowing into Matsumae, we can conclude that the Ainu of Hokkaido were the masters of an immense maritime network at the dawn of the seventeenth century. To the east, they braved the fog shrouded Kuril Islands, returning with the softest furs and the feathers of eagles. To the north, their influence stretched across the straits to Sakhalin, where they acted as the vital link between the Japanese frontier and the silk-laden outposts of the Ming Empire.

The Land of Yezo was never the desolate wilderness the maps suggested, it was a sophisticated theatre of exchange, connecting the heart of Asia to the far reaches of the Pacific.

The frost-bitten horizons of the seventeenth century were shifting. While the world looked toward the Americas, the Russian Empire was clawing its way east, eyes fixed on the rising sun. This is the chronicle of the men who pushed through the Siberian ice to find a hidden empire of the sea.

The Ghost of the South: Vladimir Atlasov

In 1697, Vladimir Atlasov pushed deeper into the jagged wilds of Siberia and Kamchatka than any Russian before him. His mission was simple, find the end of the world. In the central plains, he fought the elements and encountered the indigenous Kamchadal, but it was at the peninsula’s southern tip that he found a mystery.

There stood a people with faces unlike any he had seen, men with thick beards and striking features. He dubbed them the “Kuril,” though we now know them as the Ainu. When Atlasov finally staggered back to the outpost at Yakutsk, he brought a startling report. Kamchatka was not the end of the known world. Boats arrived from a chain of islands to the south, laden with pottery and fine cotton textiles. The frontier was wider than the Tsar had ever dreamed.

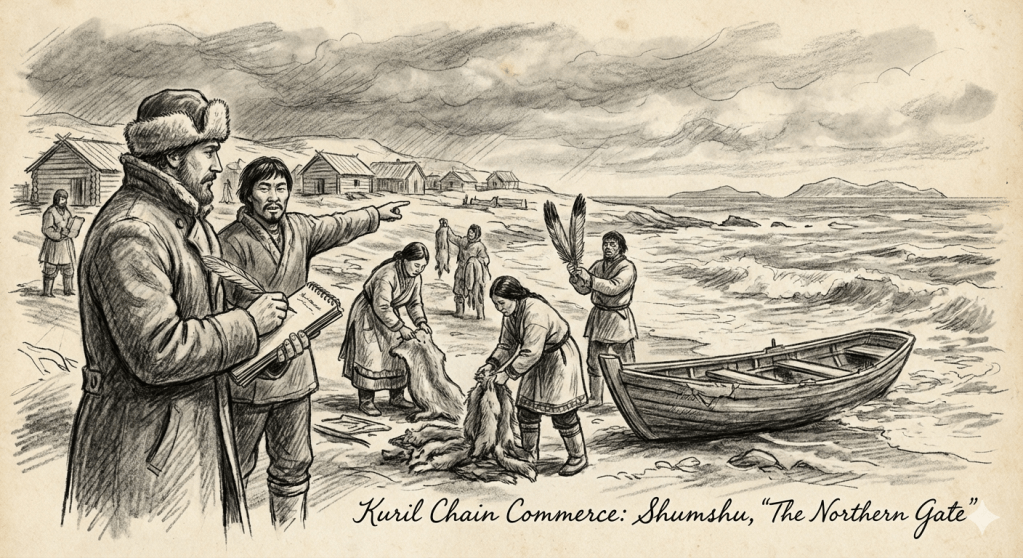

The news ignited a fire in the Russian government. They wanted those islands. In 1711, the explorer Ivan Kozyrevsky set off from the Kamchatka Peninsula, cut through the freezing surf to land on Shumshu, the first of the island chain. Two years later, he pushed further to Paramushir.

It was there, amidst the volcanic ash and crashing waves, that he had a chance encounter that would change history. He met a man named Shatanoi, a merchant who had travelled hundreds of miles from the island of Iturup far to the south.

Shatanoi was one of the Kuril, the Ainu, and he carried the secrets of the Pacific in his head. Through him, Kozyrevsky peered into a world of “lively commerce” that the West had never seen.

Shatanoi described a vast maritime highway where Ainu sailors navigated treacherous currents to link the southern tip of Kamchatka to the Kuril Islands and down to the great land of Hokkaido. They weren’t just survivors, they were the middlemen of the North Pacific, moving goods between empires while the rest of the world still thought these waters were empty.

‘I stood upon the wind-whipped shores of the Kuril chain, recording a world of commerce that would leave the bureaucrats in Yakutsk breathless. My guide, Shatanoi, helped me map this northern labyrinth, where every island serves as a quay for an empire of trade. This is what I have observed and documented. On the first island, Shumshu, I found the Kuril people living amidst the salt and spray. They are the keepers of the northern gate.

Travelers from the distant southern islands arrive here specifically to gather the riches of the cold: sea otter pelts, fox furs, and those fierce eagle feathers the warriors prize for their arrows.

Moving to the second island, Paramushir, the trade grows even more sophisticated. Here, the Kuril arrive from the remote reaches of the south, their boats laden not with raw furs, but with luxuries, fine silk, sturdy cotton textiles, iron swords, cooking pots, and delicate ceramics. It is a mirror of civilization in the middle of the sea. The people of the third island, Onekotan, are the true linguists of the north. They sail frequently to the Kamchatka mainland to hunt for pelts, and because they trade and intermarry so freely with the Kamchadal, they speak their tongue as if it were their own. I saw many Kamchadal women among them, and heard of many Kuril daughters sent to the mainland to wed.

By the time I reached the fifth island, Shiashkotan, I realized I had found the great crossroads. This island is a neutral meeting ground, a bustling market where the men of the north and the southern traders from Iturup gather to strike their bargains.

The scale of their ambition is staggering. The inhabitants of Urup, far to the south, sail even further to Kunashir. There, they buy the silk and cotton that eventually makes its way north to Paramushir in exchange for more furs and feathers.

But it is the men of Iturup who truly command the waves. I have learned that they are not content with local trade, they navigate the entire length of this volcanic chain, traveling all the way from the southern reaches to the very shores of Kamchatka. They are the masters of this maritime highway.’

Kozyrevsky had finally reached the southernmost point of the Kuril island chain. It is a realm where the frozen north finally meets the sophisticated edge of the Japanese Empire. Guides spoke with reverence of the lands that lay beyond the horizon, describing a chain of commerce that defies the imagination.

With only one more island before the Japanese frontier. Kunashir, a vital hub where the wilderness ends and the world of the Shogun begins. Here, traders from the great land of Matmai (Matsumae) arrive in small, agile boats. They come seeking the symbols of power, live eagles and the feathers that grace the arrows of lords. In return, they offer the riches of civilization shimmering silk, sturdy cotton, and iron pots.

But the Kuril of Kunashir are not mere observers, they are bold sailors who frequently navigate the straits to Matmai themselves. This Matmai is the fifteenth and largest of all the islands. It is a giant of the sea. While it is the ancestral home of the Yezojin, its southwestern coast holds a prize of stone and timber and a Japanese town, called Matmai.

In the markets of this town the trade is fierce and dazzling. The Yezojin buy Japanese swords, lacquerware, and rolls of fine textile. They haul these treasures back across the waves to Kunashir, using them as currency to buy the sea otter and fox pelts that eventually find their way back to us in the north.

A Century of Connection

Looking at their notes and the rough maps drawn by my predecessors, de Angelis and Carvalho, the truth becomes undeniable. This is no new discovery, this “Silk Road of the Sea” has been pulsing with life since medieval times.

The mystery of the strangers mentioned by de Angelis, those two visitors who arrived in Matsumae a hundred years ago speaking an unknown tongue is a mystery no more. Based on the geography and notes of the Jesuits and Russian explorers, they were undoubtedly Kamchadal people, from the mainland of Kamchatka.

From the shores of Kamchatka to the castle walls of Matsumae, the Sea of Okhotsk is not a barrier, but a highway. And at the centre of it all, are the Ainu, the boldest mariners of the north, whose trade networks have linked empires and ethnicities for centuries.

End

Stuart Iles

Edited and images by Gemini AI.

You must be logged in to post a comment.