Ancient Envoys and Seafarers of Japan

by Stu.

In the very early history of Japan, despite the perilous nature of sea travel, Japanese envoys bravely sailed to China (Sui Dynasty) to immerse themselves in studies of social stratification, diplomacy, and commerce, thereby laying crucial groundwork for Japan’s developing concepts of nation building. These people were members of envoys sent to the Sui (581-618AD) and Tang (618-907) dynasties. Little did they know at the time, that their roles in Japanese history would have a profound impact on the foundations of Japanese culture.

The Sui dynasty was an Imperial power founded in 581AD, re-unifying much of the old Jin Dynasty lands as well as the northern lands that were mostly small kingdoms that had been at constant conflict. In the meantime, within Japan there was a movement towards unification centered around the Yamato people. The Yamatai people had developed into a small number of kingdoms which included Yamato, Izumo, Kibi, Kumaso and the Hayato. In the second or third century, these small villages begin to unite around the Yamato court and as time progressed, this movement eventually spread to the far eastern provinces where Empress Suiko and Prince Shotoku ruled. The establishment of Buddhism was solidified during the rule of Suiko, she fostered its growth through the financial support of temples and monasteries and by formally institutionalizing Buddhist worship formally acknowledged in the second article of the seventeen article constitution.

Suiko’s rule was also marked by dramatic systemic change. It was during her reign that China officially recognized Japan diplomatically, spurring an increase in Chinese influence that saw the adoption of the Sui bureaucratic system of government and class nobility. To facilitate these changes, envoys from the Sui arrived in Japan consisting of monks, artists, and scholars. Meanwhile, the growing prominence of Buddhism, also introduced through the Korea peninsula, strengthened Korean cultural and artistic influence within the Yamatai. Writing systems even reflected this by assigning previous emperors Buddhist names using Korean pronunciation. Ultimately, these domestic and foreign developments led to a consolidation of the emperor’s and nobility power in Japan.

Around the same time other kingdoms were also adopting Sui culture, religion and writing systems. The three kingdoms, Goguryeo, Baekje, and Silla on the Korean peninsula were under a tribute system with the Sui. As they were subordinate to the Sui Dynasty, traders presented gifts to the Sui emperor and the royal court upon their envoy’s arrival in the capital Chang-an.

The first Japanese envoy sent to the Sui dynasty was in the year 600 but strangely, the second envoy from 607 is more famous, led by Ono no Imoko. Ono was sent with a letter from Prince Shotoku which said. ‘From the son of the Land of the Rising Sun, to the son of Heaven the land where the Sun Sets, are you well?’ Emperor Yang of the Sui Dynasty, according to Chinese ideology, the emperor receives a Mandate of Heaven and rules over neighbouring countries. There must be, only one son of Heaven or in this case, one emperor. In his short but sweet introduction, Shotoku believed that being recognized by the son of heaven by the Chinese emperor, the Yamatai Emperor would gain authority and become even more of a symbol in a new united nation. But why was this necessary from Shotoku?

On the Japanese peninsula, if an independent kingdom, one which had not necessarily submitted to the Yamatai Court at the time, were to independently enter into a three-way tributary system with the Sui Dynasty, and be recognized as an independent nation, it would hinder the Yamatai court future endeavours to consolidate their rule. To prevent this, Shotoku had to be recognized as the emperor of the Japanese nation by the Sui. Although Emperor Yang was angry when receiving the letter, Ono no Imoko returned to Japan unharmed. However, Emperor Yang decided to send a Sui envoy named Pei Shiqing and his entourage with him, as the Sui Emperor had his own ulterior motive. On the northern Korean peninsula, tensions were brewing, along the Goguryeo border region. To keep them in check Yang probably decided that it would be better to have Baekje to the south and the Yamatai in Japan on their side if needed. Although, it seems that the Sui Dynasty never recognized Shotoku as the Emperor from the Rising Sun. This is because there was an incident in which Ono said that he had misplaced the letter from Emperor Yang on his journey back to Japan. We do not know if Ono’s story is fabricated or not. Of course, Shotoku was not satisfied with the reply from the envoy however Shotoku and the court wanted to publicize the Sui mission as a success domestically so the case was swept under the carpet, so to say. In any case, there was one more envoy sent to the Sui in 618, Ono accompanied Pei on his return trip back to the Chinese capital Luoyang, after a successful trip to Japan. War had broken out with the Goguryeo which drained the Sui coffers. Yang increased taxes to help pay for revenue losses but the war was lost. Yang lost favour of the people and military which resulted in a revolt against the Sui, Yang was assassinated which brought about an end to the Sui Dynasty.

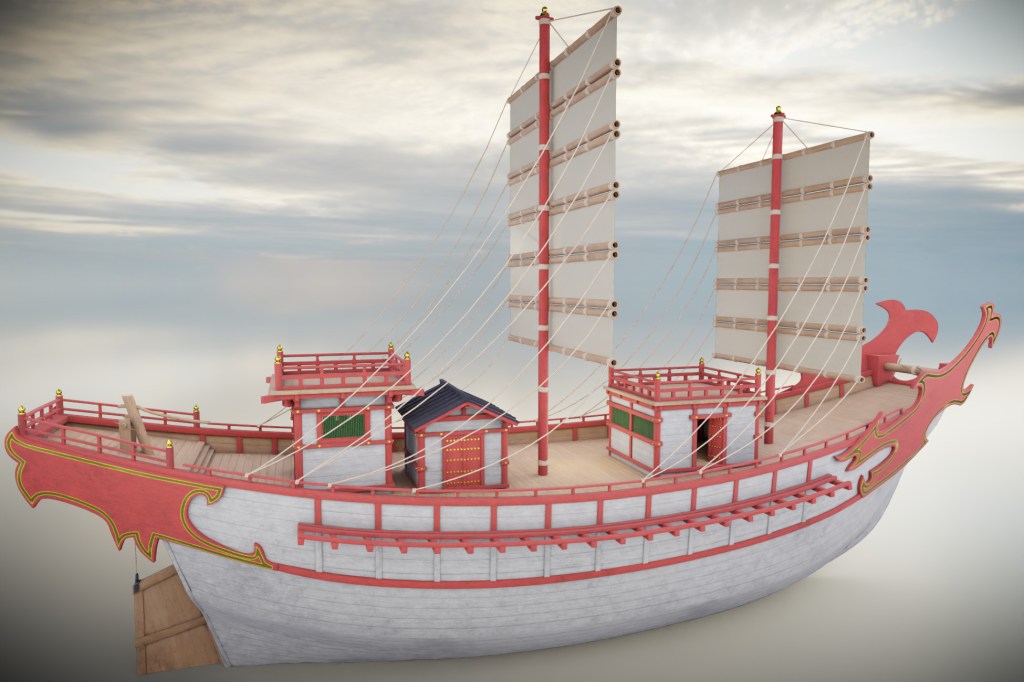

The Tang Dynasty was established by Li Yuan, a Sui military general how had participated in the revolt. The first envoy to the Tang departed in 630 which became known as Kentoshi mission. For us who research history, this mission is a wealth of information. This the first mission which gives us more details about the route and number of people taking part. The mission left Osaka in 630 and returned in 632. Ships departed Osaka which sailed through the Seto Inland Sea, with a final stop in Hakata before making the trip across to the mainland. The mission consisted of the ambassador, his emissaries, an entourage of students, monks and others totalling up to 500 people. This was the largest envoy that the Japanese had sent to China. As with previous missions to the Sui, the Tang mission goals were to study its government and legal systems, economic practices, culture, and religion, particularly Buddhism, but these missions were on a much larger scale than in the past. Embarking on such a high risk journey wasn’t without its dangers either. Open water seafaring was still a major risk along with malnutrition, war and disease. It is said that up to one third of people who set out on these envoys did not return home. 20 such missions were sent over a period of 40 years but the Battle of Baekgang in 663 (Battle of Hakusukinoe in Japanese) marked a major suspension for future missions. The Battle of Baekgang was central to restore power to the Paekche kingdom along with their Yamato ally against the allied forces of Silla and Tang. I’ll just give a little background information here.

A naval battle took place in 663 between the combined forces of the Yamatai and Baekje, and the combined forces of Tang China and Silla. The Japanese navy was defeated, losing its foothold on the Korean Peninsula.

The Yamatai regime had maintained a foothold in the southern part of the Korean Peninsula and enjoyed friendly relations with the Baekje nobility. Many cultural influences, such as the adoption of Buddhism came through Baekje to Japan. When Baekje was conquered by Silla, Japan dispatched a naval force to help with its restoration, however suffered a crushing defeat.

Previously, when Baekje was attacked and fell to Silla in 660, The Yamato court raised an army to aid Baekje, but before they could leave Kyushu, the campaign was suspended as Empress Saimei died in Tsukushi. Shortly later, when Prince Naka no Ōe ascended the throne and became Emperor Tenji, he sent a naval force in 663 to help the restoration forces of Baekje, fighting the combined Tang-Silla. The battle resulted in a disastrous defeat for the Yamatai, with almost total annihilation. This defeat caused Japan to completely lose its foothold on the Korean Peninsula, which also kicked off construction of mountain fortresses on Tsushima and Kyushu, in the case of a Silla attack.

The Silla invasion never eventuated and things went quiet for nearly 40 years. In 702, a Yamato envoy was assembled and sent to China. The purpose of the mission was to normalize diplomatic relations once again, and the Tang were open to accept the mission. In fact, after the battle in 663 relations between the Tang Dynasty and Silla actually deteriorated so it was beneficial for the Tang to re-establish connections with the Yamato in order to keep Sila in check. As with the Sui Dynasty before, the Tang Dynasty established a system of strict tributary relations with neighbouring kingdoms.

The main purpose of this tributary rule was to enter into a new era. The surrounding kingdoms under the tributary system adopted the same urban planning and political systems as the Tang Dynasty and when compiling their own national histories, they told to follow the format that had been used in ancient China and which also accepted Buddhism as their national belief system. In order to normalize diplomatic relations with Japan, they were also required to follow the example of the Tang Dynasty along with their own revival. The successful mission kicked off a new era in Japan with a lot of changes to take place within the Yamato court.

In the past in was customary for the Yamato capital, usually a palace, to move once the rule of a new emperor or empress began. Therefore, until the Heijo-kyo was built in 710 the capital was continuously moving. Encouraged by the 702 mission to the Tang, Empress Genmei ordered the Imperial capital to move from Fujiwara-kyō to Heijō-kyō in Nara in 708, and the move was completed in 710. Heijō-kyō was designed identically to the Tang capital, Chang’an, the only notable difference being that the Japanese capital didn’t have stone walls to protect the city. Once built, the city flourished, and the population grew quickly to over 50,000 residents and also attracted foreign envoys from, the Tang, the Korean kingdoms and envoys from as far as India. Heijo-kyo became a trade centre as the last stop along the Silk Road.

Life of the envoy.

The majority of people who served in envoys to China would return home after 1 or 2 years but some students who accompanied them stayed on longer and studied for nearly 20 years in their adopted home. After graduating, students become government officials and advisors, some even got married and started families in China. Until the arrival of the following envoy, the Tang emperor covered all tuition costs and expenses for the students who eventually graduate to become government-sponsored students. In addition, Heijo court rankings and social status were transferred directly to Tang society. Those students of the Yamato aristocracy could attend the government examinations which were usually only available to the Tang nobility.

From the diary of envoy Kibi no Makibi, a long term student in Chang’an who returned to Nara and became a scholar and a noble in the Heijo court. ‘Looking back at the heavens I see the Moon Rising over Mount Mikasa in Kasuga. I came from a family of lower ranked ministers so I entered the Shimongako, which was a school for commoners or those of the lower ranked nobility.’ However, on his return to Japan in 735, he entered into Heijo court as a much higher ranked official than he would have achieved without studying in China. Makibi also fell in favour of Emperor Shomu who called him, Togu Gakushi, or the Scholar of the Eastern Palace where Makibi lectured.

Officials, envoys and students from Japan were allowed to marry in the Tang capital. Fathers of children were allowed to take their children back to Japan when their service finished however, they were not allowed to take their wives. One official, Fujiwara no Kiyokawa crossed the sea as a Japanese envoy to Tang arriving in 752 along with Otomo no Komaro and Kibi no Makibi returning once more after a falling out with Fujiwara no Nakamaro (Chancellor of the State). Makibi was promoted to Junior Forth Rank but a power struggle between him and Nakamaro developed when Makibi openly supporting Shomu’s daughter (Empress Koken), and his student, to the throne. Makibi was initially expelled to Dazaifu in Kyushu but later took up the assistant envoy to the Tang with Fujiwara no Kiyokawa. Makibi returned to Japan in 754 and promoted to the rank of Junior Third Rank in Dazaifu.

However, Fujiwara no Kiyokawa was unable to return home due to an incredible series of events. Two ships left China after a successful mission however, the ships hit a storm shortly after departing, one ship got through it, but the ship Fujiwara was aboard was blown off course and wrecked on the coast of today’s Vietnam. Fighting off bandits and then having to deal with disease, most of the crew and delegates perished, but Fujiwara made it back to Chang’an the following year. A second return trip was planned in 759 but this was also put on hold due to the developing An Lushan Rebellion (755-763). Fujiwara no Kiyokawa accepted his fate, took a new name Heqing and was given the position, Chief of the Secretary Ministry. Fujiwara stayed on, in Chang’an until an envoy arrived in 777. Unfortunately, Fujiwara died in 778 just as the envy were preparing to return to Japan. During his unintended long stay in China, Fujiwara married the daughter of a Chinese noble and had a daughter named Kijo, who travelled to Japan with the returning envoy.

When students and diplomats returned home from China, not only did they return with a wealth of experience and information, they also brought back Buddhist scripts and enough books to stock a library. So many, in fact that the route from Chang’an to Nara became known as the book road. Japanese culture and society at that time was considered as primitive by the Chinese. All the envoys including students who had been educated in China were now able to pass on all of this information as well as translate out text into Japanese that could be read by Japanese court nobles and the aristocracy. It was known at that time that if Japan wanted to modernize, its people had to travel west.

Hundreds of Japanese envoys were sent to Tang China who brought back an uncountable number of treasures, but it is by no means the case that Japan accepted every single detail. The Tang Dynasty’s imperial system was adopted by the Japanese but perfected into what we now recognise as the Ritsuryo system. The court built a new capital city modelled on Chang’an and compiled a list of national history and annual events such as the Seven Herbs Festival and Hina Matsuri which were adapted from the Tang which has now become a part of Japanese life. Near Dazaifu, in modern day Fukuoka city, a facility called the Korokan was built modelled after the Tang, Kouro-ji temple. This facility served as an envoy guesthouse for diplomats/traders and scholars coming to Dazaifu in Kyushu.

The Nara court accepted Buddhism and Confucianism but they rejected Taoism. The Imperial examination and eunuch systems who served the royal court were also rejected. The nobility were quite selective about what they could adapted to suit Japanese culture. During this time Nara, like Chang’an was an intentional capital, many people came from the Korean Peninsula and China even as far away as Persia.

Documents from the time show that people came from China and Korea and in a census compiled during the Heian period which recorded the origins of surnames. Approximately 25% of the surnames listed were immigrants. Some say that Japan was an international country during this period and there’s no doubt that Japanese envoys to Tang China contributed to the number of foreigners in places like Hakata, which is traditionally known as the gateway to Japan as well as Nara.

At that time crossing the seas to the continent was a life-threatening endeavour, due to piracy, illness and of course, the weather. When diplomatic relations with the kingdoms on the Korean Peninsula were good, ships followed that the Korean peninsula to the north, hugging the coastline, but after the battle of Battle of Baekgang in 663, relations deteriorated so the route became dangerous. Therefore, ships set out from Hakata to the Goto Islands, Ryukyu (Okinawa) then on to the mouth of the Yangtze. Some tried a direct route from Hakata directly south west but this route was the most dangerous. It is said that 20 to 30% of envoys were lost at sea. Each mission to China consisted of around 500 people so it’s not difficult to imagine that many talented people’s lives were lost. Envoys also faced losing their lives to diseases such as smallpox and even if an envoy or student completed their studies in China, some people like Fujiwara Kiyokawa never returned home.

藍瑠杜

Source

歴史街道 令和6年5月

You must be logged in to post a comment.